This article is from the weekly “State of the Network” newsletter of Coin Metrics, an institutional provider of cryptocurrency data and analytics. For the English original version, please click here. For more info about Coin Metrics, email info@coinmetrics.io

Article creator : Karim Helmy and the Coin Metrics Team

Date : May 19th, 2020

Key Takeaways

- Block rewards are currently the primary source of revenue for miners. A reduction in this reward due to the halving causes some miners to exit the network. In the short term the sudden drop-off of miners can potentially leave the network more exposed to security threats like 51% attacks.

- The distribution of hashpower among different types of mining hardware also has an impact on the network’s security properties. The availability of old hardware on secondary markets poses a potential threat to the network.

- Novel techniques involving nonce distributions allow us to numerically estimate the amount of hashpower provided by certain types of hardware, including older hardware like S7s and S9s.

- It now appears that a significant number of formerly-offline S9s have been turned back on. Currently, the Antminer S9 family of miners is responsible for about 32% of Bitcoin’s hashpower.

- While the amount of hashpower that could be created by offline S9s is nowhere near enough to 51% attack the network, the change to the network’s security dynamics caused by their presence is significant.

Halving a Good Time

On May 11th, for the third time in Bitcoin’s history, the amount of new coins issued per block was cut in half. This event, known as the halving, occurs every 210,000 blocks, or approximately four years, until issuance is eventually rounded down to zero.

In the most recent halving, the block reward was reduced from 12.5 to 6.25 BTC. The period leading up to the halving was marked by pronounced market volatility, which has somewhat subsided since the reduction occurred. The impacts of the event on the network’s security are nuanced.

Block rewards are currently the primary source of revenue for miners, so a reduction in this reward causes some miners to exit the network. With less revenue to go around, margins are tightened and less efficient miners may suddenly find themselves operating at a loss. In the long run, these miners are typically replaced by more efficient operations as the market rebalances. In the short term, however, the sudden drop-off of miners can leave the network more exposed to security threats like 51% attacks.

State of the Network Issue 44 reasoned about the impacts of the halving on miner economics from first principles. This piece will address a similar topic, focusing on the implications of the halving on security and the economics of running old mining hardware. In the process, we’ll use nonce data to estimate the prevalence of certain types of hardware on the network today, and discuss how the presence of old hardware impacts Bitcoin’s security model.

To Halve and to Secure

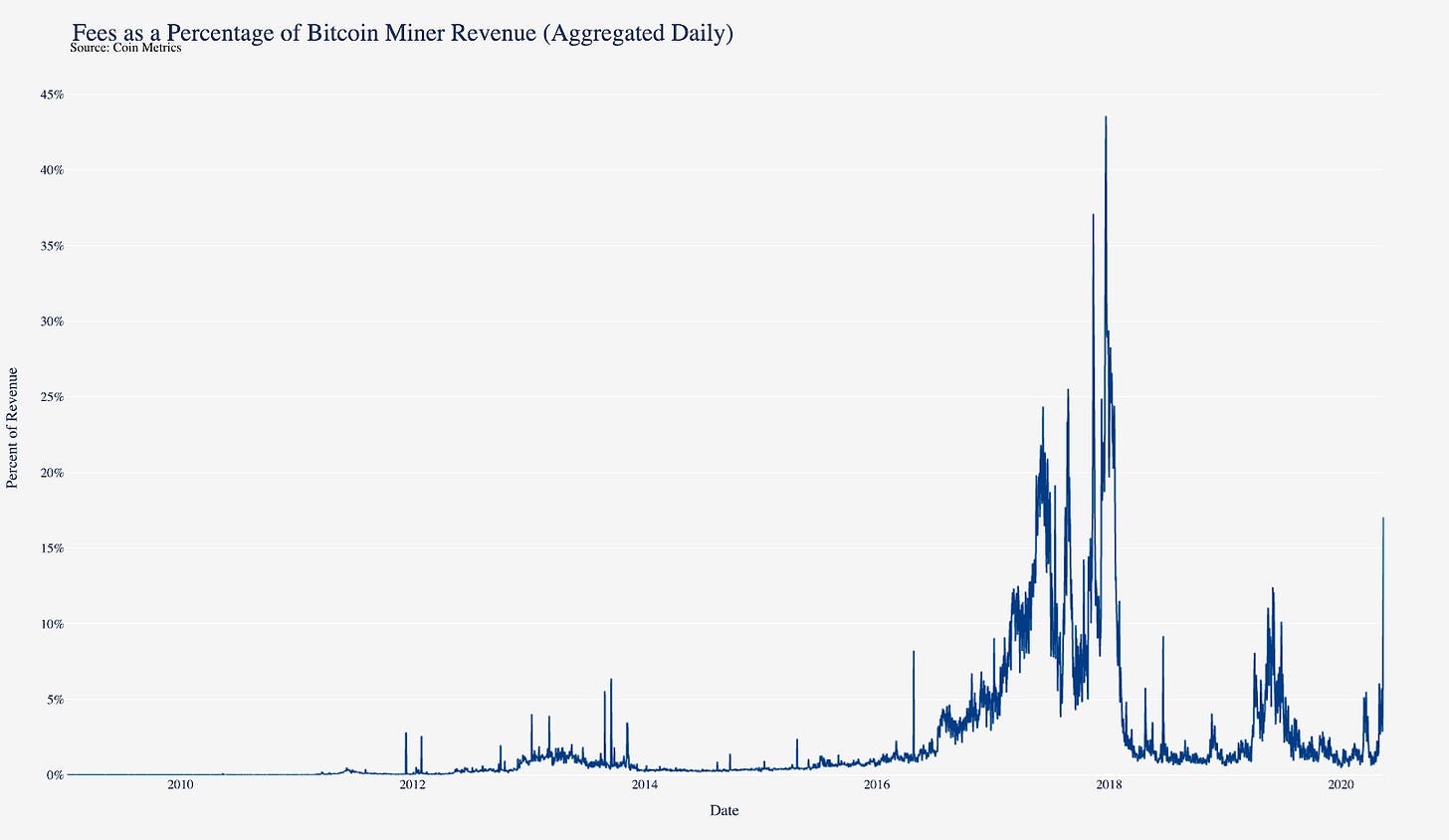

Bitcoin miners are compensated through both block rewards, which are directly affected by the halving, and transaction fees, which are not. Transaction fees are generally a function of demand for block space, and therefore tend to spike during periods of congestion and high traffic.

Currently, fees make up a small percentage of total miner revenue. Over the past five years, only about 4.4% of miner revenue has been generated from fees.

Source: Coin Metrics Network Data Pro

As Bitcoin’s block reward continues to halve approximately every four years, transaction fees will need to increase in order to sufficiently incentivize miners to secure the chain. Since slightly before the halving, fees have surged to make up about 17% of total miner revenue. While this effect has been intensified by the reduction in the block reward, transaction fees themselves have also increased to levels not seen in almost a year.

This increase in fees may have been amplified by the reduction in hash rate that has taken place since the halving. This reduction, in turn, is caused by less efficient miners leaving the network. The drop in hashpower has increased the time between blocks, therefore reducing the amount of available block space.

To reduce the variance of their payouts, miners often aggregate into mining pools, which are loose coalitions of miners that are organized by an operator and share revenue, typically according to hashpower contribution. Individual miners often switch between pools depending on several factors, most notably fees charged by operators.

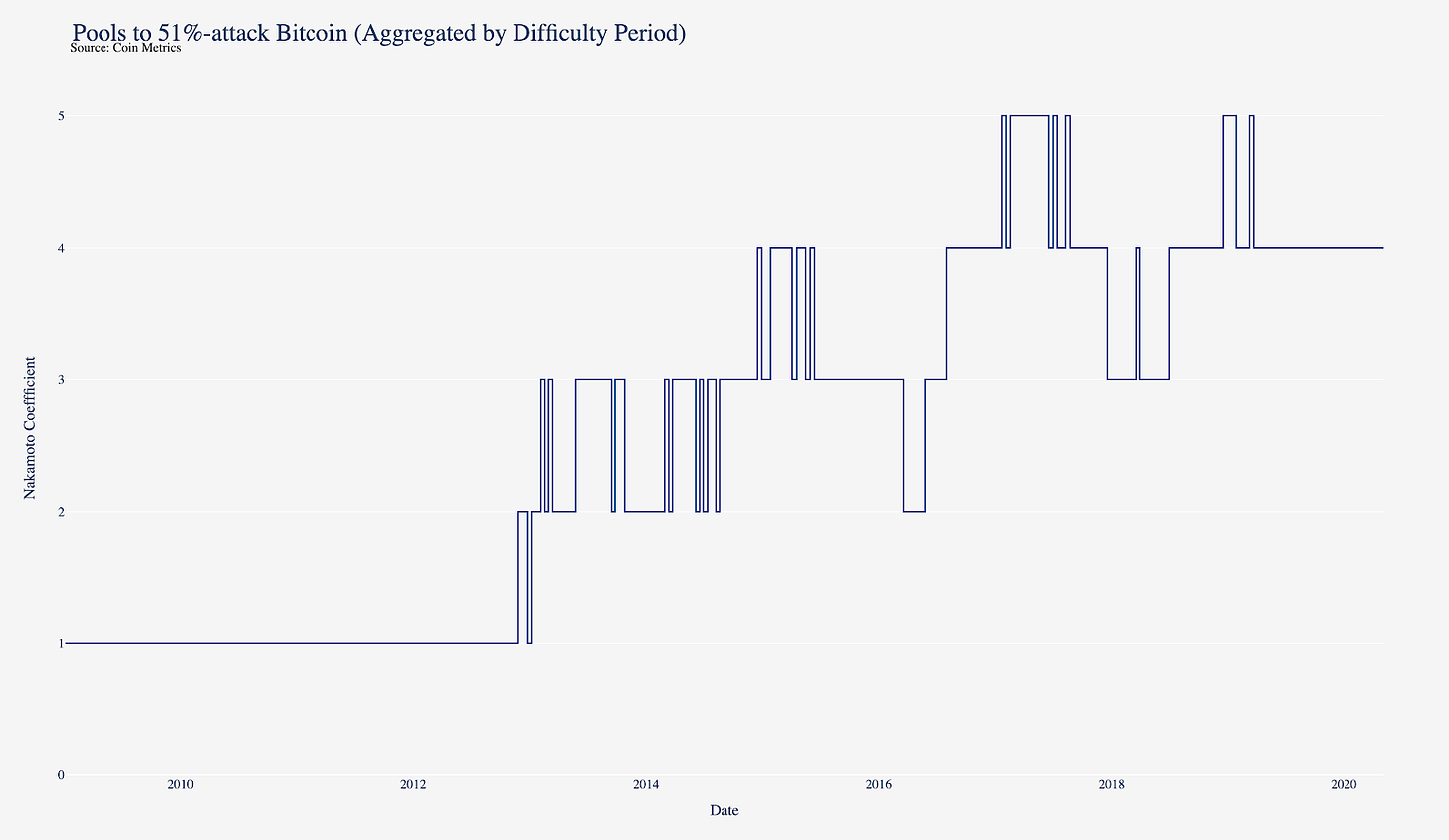

As long as no single dishonest entity controls more than half of Bitcoin’s hashpower, the network is secure. In a process known as a 51% attack, an adversary who controls more than half the network’s hashpower can censor transactions and perform double-spends.

The minimum number of pools who would need to collude in order to 51% attack the network is known as the Nakamoto coefficient. At this time, the top 4 pools would need to collude in order to 51% attack the network. This number has generally gone up over the course of Bitcoin’s history, indicating a steady increase in decentralization.

The Nakamoto coefficient is not a perfect metric, and makes Bitcoin seem significantly more centralized than it is. Individual miners, who face large up-front expenses on capital like hardware, are disincentivized from attacking the network. These miners would likely defect from a maliciously-operated pool.

Still, pools select the blocks that their constituents mine, and barring defection exercise a certain degree of control over them. It also may be possible for an attacker to censor transactions with less than half of the network’s hashpower through techniques like feather-forking. It’s therefore useful to have a pessimistic metric like the Nakamoto coefficient to quantify the degree of centralization among miners.

Stratum V2, an implementation of Betterhash with modifications to the original protocol, suggests letting individual miners select the blocks that they will mine, rather than the pool operators doing so. This potential improvement to the way pools are operated would put more power in the hands of individual miners, further decentralizing the network.

In addition to the distribution of hashpower among different entities, the distribution of hashpower among different types of mining hardware has a significant impact on the network’s security properties.

Hardening Hardware

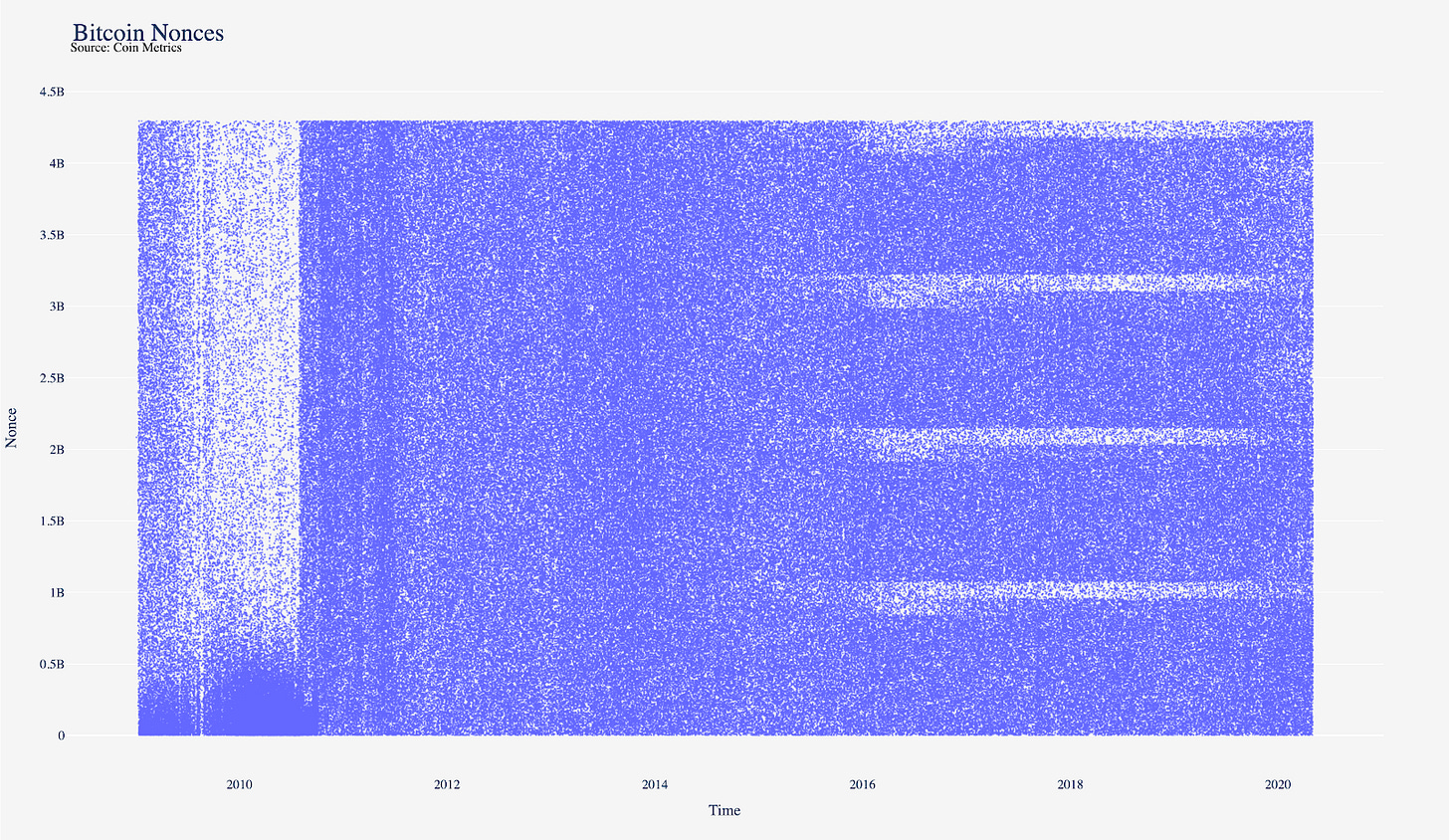

To add a block to the blockchain, Bitcoin miners attempt to find a nonce, or arbitrary value, that causes the block header to hash to below a certain target. The rate at which these hashes are computed and verified is known as hashpower, and a nonce satisfying this condition is called a golden nonce. Golden nonces are theoretically uniformly distributed throughout the space of potential nonces and valid blocks. The threshold that the hash of the block header must satisfy is set by the network’s difficulty parameter, which is periodically adjusted according to the rate at which blocks have been accepted to the chain.

While mining was initially performed with CPUs, the process was parallelized and made more efficient early-on through the adoption of GPUs. Today, almost all mining is performed using mining rigs that contain specialized chips known as ASICS. These devices are significantly faster, better at parallelization, and more energy-efficient than other hardware.

Purchasing these devices requires a large up-front capital expenditure. This benefits the security of the network by requiring miners to lock up capital in an illiquid asset and therefore disincentivizing them from acting maliciously.

The presence of old mining hardware changes this security model, since it tends to require smaller up-front investment at the expense of higher operating costs. While there are practical and logistical barriers to starting a mining farm aside from the cost of hardware, the presence of old hardware allows entry into the market with significantly reduced capital expenditure.

Due to secrecy in the mining industry, it’s generally difficult to discern which types of mining hardware are being used to secure the network. However, novel techniques allow us to numerically estimate the amount of hashpower provided by certain types of hardware.

Bitcoin’s nonce distribution offers hints at the types of hardware being used to mine on the network. By combining this data with information on the prices of hardware on secondary markets, we can quantify the degree of risk posed by the existence of inexpensive, slightly dated hardware. For a detailed explanation of our analysis of nonce distributions, see our series “The Signal and the Nonce” Part 1 and Part 2.

Since golden nonces are uniformly distributed throughout the nonce spaces of all potential blocks, we’d expect a plot of the winning nonces over time to look like random static. Bitcoin’s nonce distribution doesn’t.

Near the left-hand side of the plot, nonces are concentrated in the lower ranges of the distribution. This is a result of a sampling technique used by miners in the CPU-mining era, which involved iteratively testing values starting from zero and incrementing upward.

Bitcoin’s nonce distribution also has a characteristic streaked pattern that first appeared in late 2015, and has recently begun to fade. The striations in question start out broad, and then suddenly narrow out, before gradually fading away. There are four distinct streaks, each of which can be specified in terms of its narrow and wide bands.

These streaks were noted in State of the Network Issue 23, and their source was identified in State of the Network Issue 45. The striations were found to come from the way in which nonces are sampled by the Bitmain Antminer S7 and S9 mining rig lines. Each of these rigs was at one point the dominant miner on the network, with the S9 having recently been supplanted in this role by the Antminer S17.

The wide and narrow bands are attributable to the sampling techniques used by the S7 and S9 families, respectively. We can use this knowledge to numerically estimate the proportion of the network’s hashpower provided by S7s and S9s.

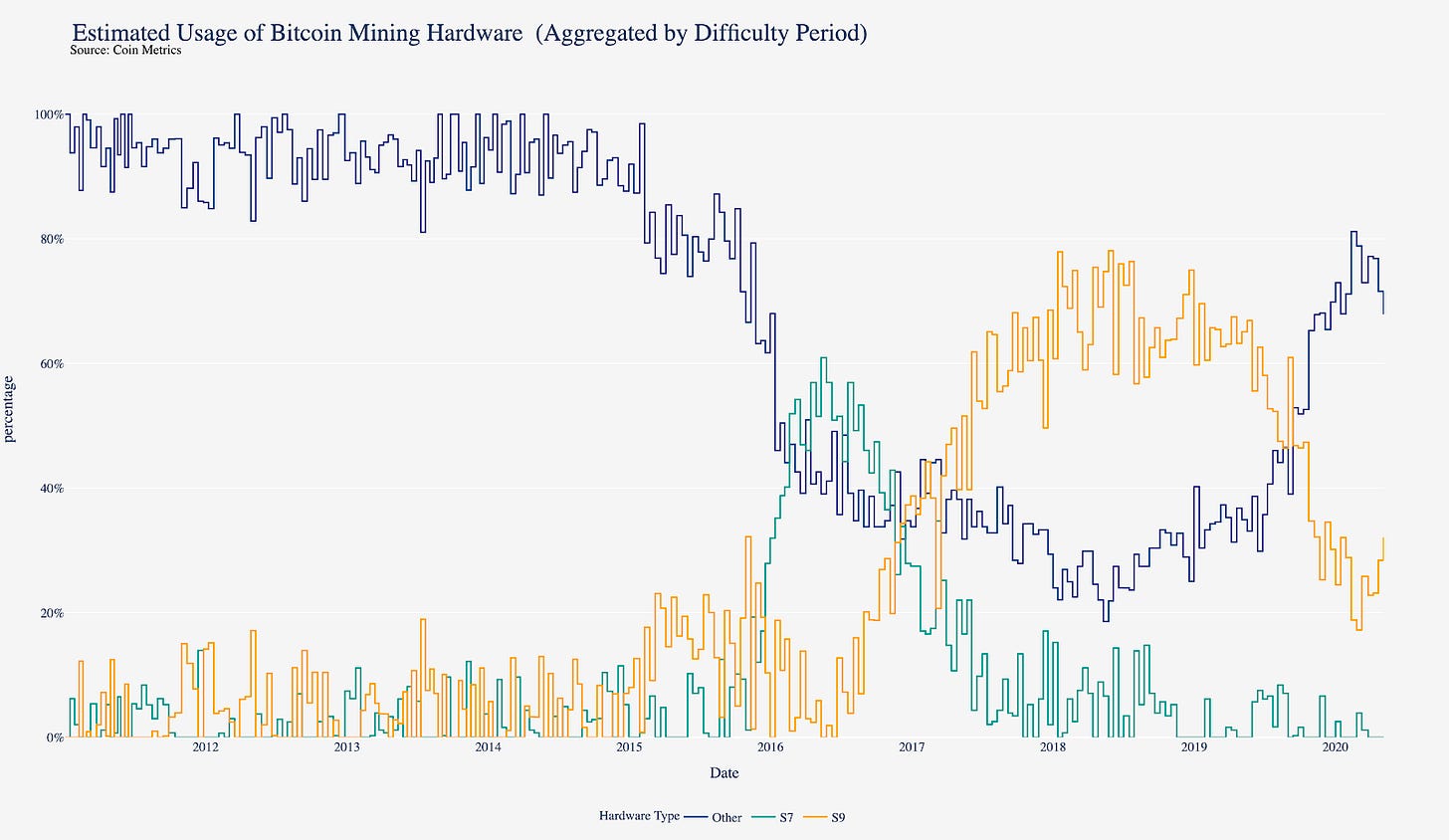

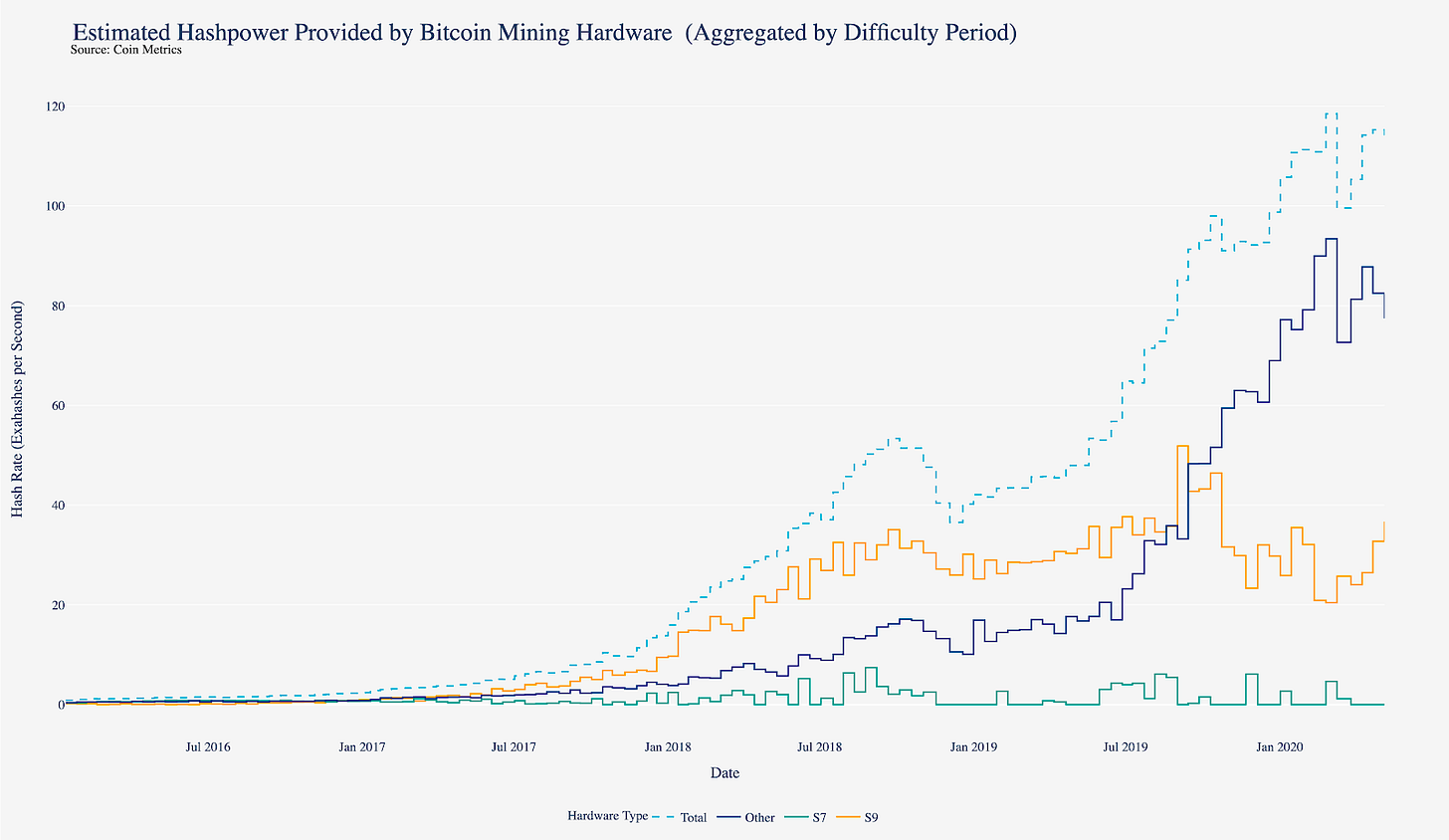

According to these numerical estimates, the proportion of hash rate provided by S7s and related hardware peaked in May of 2016 at about 61%. Today, S7s are not responsible for a significant portion of hashpower. The proportion of blocks mined by S9s and related hardware peaked in May of 2018 at about 78%. Today, about 32% of blocks are produced by S9s.

These estimates are based on the assumption that S7s and S9s do not sample within their respective excluded bands and that all miners sample uniformly outside of any excluded regions. These conditions are violated in the CPU-mining era, but appear to hold from the GPU-mining period onward. The excluded regions are determined manually, and estimates are corrected for any extrapolated values outside of the 0-100% range and normalized.

The estimates are subject to a certain amount of noise, which is visible toward the left of the graph. The small bump in the estimated proportion of S9 hashpower in 2015 could be due to noise, or may be a sign of something else such as the testing of experimental hardware.

These figures are consistent with other estimates of the hashpower output of these types of hardware. A CoinShares report on Bitcoin mining released in December 2019 estimated that S9s made up about two thirds of the hardware in their equivalence class. In March, the founder of Beijing-based Spark Capital estimated that S9s provided 20 to 25 percent of Bitcoin’s hashpower.

The proportion of hashpower provided by each type of mining rig provides further perspective on the threat posed by old hardware.

The most salient insight from this plot is the exponential growth in the hashpower securing the network.

The estimated amount of hashpower provided by S9s reached its peak in August of 2019, when they generated about 52 exahashes per second. In February of 2020, the estimated hashpower generated by S9s reached the bottom of a valley at about 21 exahashes per second.

It now appears that a significant number of formerly-offline S9s have been turned back on, likely as a result of a recent appreciation in the price of Bitcoin. This hardware now computes about 37 exahashes per second.

Due to rapidly changing market conditions, this effect may not be sustained. However, it illustrates the degree to which mining with old hardware may be viable given favorable conditions, and the ease with which this less-expensive hardware can be deployed.

S9s are being sold on secondary markets for a fraction of their retail price. The miners can be purchased for between $20 and $80, compared to an original price of about $3000. Given today’s economic climate and the inexpensive electricity brought on by China’s rainy season, miners have found it possible to operate these devices profitably.

While the amount of hashpower that could be created by offline S9s is nowhere near enough to 51% attack Bitcoin, the change to the network’s security dynamics caused by their presence is significant. This effect may be felt more acutely by other platforms that use Bitcoin’s proof of work algorithm, including Bitcoin Cash and Bitcoin SV, which are currently secured by about 2.5 and 1.8 exahashes per second of computational power, respectively.

The Epitaph of the Third Epoch

In anticipation of the halving and on optimism related to increased institutional interest, the price of Bitcoin increased dramatically before giving up some of its gains. Since the halving, volatility has subsided somewhat, but price has continued to trend upward. The halving has also accelerated an increase in transaction fees and precipitated a slight drop in hashpower.

Halving-related sentiment will continue to impact the market, and the halving itself will continue the test of whether Bitcoin can successfully transition to a model where miners’ revenue is predominantly based on fees. The long-term effects of this event remain to be seen, but its impact on the economics of mining and the market as a whole are already pronounced.

【Disclaimer】

The Article published on this our Homepage are only for the purpose of providing information. This is not intended as a solicitation for cryptocurrency trading. Also, this article is the author’s personal opinions, and this does not represent opinion for the Company BTCBOX co.,Ltd.